What are modal verbs in German. Full, auxiliary and modal verbs in German

Modal verbs - these are verbs that express not an action, but the speaker’s attitude to the action. Modal verbs can express possibility, necessity, desire, etc.

Modal verbs require after themselves a main verb, which is in the infinitive without a particlezu.

K m Odal verbs in German include the following verbs:

durfen(to be allowed, to be able to have the right)

Darf ich eintreten? - Can I come in?

Hier darf man nicht rauchen. - You can't smoke here.

können(to be able, to be able, to have the physical ability to do something)

Wir können diese Arbeit in einer Woche erfüllen. - We can complete this job in a week.

mögen(like)

Ich magTorte essen. - I like to eat cake.

The verb mögen can also express a wish, advice, recommendation and is often translated in this case with the word “let”:

Möge er glücklich sein! — Let him be happy!

mussen(expresses necessity due to internal conviction, duty)

Ich muss meinen Freunden helfen. - I have to help my friends.

Er musste die Arbeit von neuem beginnen. - He had (he was forced) to start the work again.

sollen(expresses necessity, obligation, obligation associated with someone’s instructions, the order established by someone, etc.)

Du sollst die Prüfung am 5. Januar ablegen. - You must take this exam on January 5th.

Der Zug soll in 3 Minuten ankommen. - The train should arrive in 3 minutes.

wollen(want, wish, often with a connotation of “intend to do something”)

Wir wollen diese Ausstellung besuchen. - We want to visit this exhibition.

The verb wollen can also be used to express the future tense, in which case it is not translated into Russian.

lassen(command, instruct, force, order)

Er ließ uns diese Regel gründlich wiederholen. - He ordered us (forced us) to repeat this rule thoroughly.

Bei gutem Wetter ließ er mich selbst das Auto fahren. - If the weather was good, he allowed me to drive the car myself.

The verb lassen in the imperative mood can also express an invitation, a call:

Lasst uns heute einen Ausflug machen! - Let's take a walk today!

The construction is quite often used lassen sich+ infinitive I. It usually has a passive meaning with a connotation of possibility and is translated into Russian by combining “mozhno” with the infinitive of the main verb or a verb in -sya (with a passive meaning):

Die Bedeutung dieser Experimente lässt sich leicht erklären. - The meaning of these experiments can be easily explained (... easily explained; easily explained...).

Turnover es lässt sich with negation is used to mean impracticability, the impossibility of one or another action and is translated by combining “impossible” with the infinitive of the main verb:

Es lässt sich nicht beweisen. - This cannot be proven.

Verb lassen when used independently it means “to leave”, “to leave”:

Wir lassen ihn nicht allein. - We don't leave him alone.

Modal verbs in German are usually used in combination with the infinitive of other verbs that denote action and perform the function of a complex predicate in a sentence:

Wir wollen noch eine Fremdsprache beherrschen. - We want to master another foreign language.

Verbs brauchen(need), scheinen(seem), glauben(to believe) when used with the infinitive of another (main) verb acquire the meaning of modality. The verb brauchen with the negation nicht means “one should not, does not need, does not need to do anything”:

Er braucht diese Regel nicht zu wiederholen. - He does not need (should not) repeat this rule.

Verbs scheinen And glauben express an assumption, when translating them into Russian the words “apparently, it seems (as it seems, as it seems)” are used:

Sie scheint glücklich zu sein. - She seems (apparently) to be happy.

If you liked it, share it with your friends:

Join us onFacebook!

See also:

We suggest taking tests online:

) and irregular verbs (§ 28), in the German language there is a layer of so-called modal verbs. The features of the modal verb as such are difficult to understand for a non-linguist, so this concept itself is often used thoughtlessly. Everything here is quite simple: these verbs can express possibility, necessity, assumption, order or desire. If other verbs convey an action or state, then modal verbs express modality and reflect the speaker’s attitude to what is described in the sentence.

Modal verbs include können"to be able" durfen"to have a right", sollen"to be obliged (obliged, forced)" mussen"to have to (have a need)" wollen"want" and mögen"want". They can also drag in a verb here lassen“allow”, which in some cases expresses modality, although it is not actually modal. All these verbs belong to the group of irregular verbs, but are distinguished separately due to their lexical and grammatical features. Here we will look at the presence of verbs (preterite, see § 37). Modal verbs are characterized by the absence of personal endings in the first and third persons singular, as well as a change in the root vowel in the singular (with the exception of the verb sollen). Verb lassen conjugates as a strong with the umlaut of the root vowel in the second and third persons singular. Just memorize all these forms, repeat them and use them in conjunction with the examples. These are some of the most frequent verbs that you cannot do without in speech.

| Pronoun | Infinitive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| können | durfen | sollen | mussen | wollen | mögen | lassen | |

| ich (I) |

kann (Can) |

darf (Can) |

soll (must) |

muss (must) |

will (Want) |

mag (Wish) |

lasse (allow) |

| du (You) |

kannst (can) |

darfst (can) |

sollst (must) |

must (must) |

willst (Want) |

magst (wish) |

lässt (allow) |

| er/sie/es (he she it) |

kann (Maybe) |

darf (Maybe) |

soll (must) |

muss (must) |

will (wants) |

mag (wishes) |

lässt (allows) |

| wir (We) |

können (Can) |

durfen (Can) |

sollen (must) |

mussen (must) |

wollen (want) |

mögen (we wish) |

lassen (allow) |

| ihr (You) |

könnt (you can) |

durft (you can) |

sollt (must) |

müsst (must) |

wollt (want to) |

mögt (wish) |

lasst (allow) |

| sie/Sie (they/you) |

können (can/can) |

durfen (can/can) |

sollen (must) |

mussen (must) |

wollen (want/want) |

mögen (want/wish) |

lassen (allow/allow) |

The use of modal verbs is a topic that deserves more careful consideration. Modal verbs, like many other verbs in the German language, can express not one meaning, which is assigned to them in dictionaries, but several. Much can be gleaned from context. It should also be remembered that modal verbs, as a rule, are not used independently, but in conjunction with other verbs that complement them. In this case, they say that the modal verb is an inflected part of a compound verbal predicate. For example:

- Ich kann alles verstehen.- I can understand everything.

- Ich muss anrufen.- I need (I have to) call.

Here are the verbs können And mussen are inextricably linked with verbs verstehen And anrufen. There may be other verbs as you wish. The more often you combine, the better you remember. Here, by the way, it should be noted in advance that such expressions as “I’m hungry” and “I’m thirsty” in German, as in many other European languages, traditionally have their own formulations: “ Ich habe Hunger“/„ich bin hungrig" And " ich habe Durst“/„ich bin durstig“.

And now, in fact, let's move on to the meanings expressed by modal verbs. There are a lot of them, and you won't remember them right away, but the more often you use them, the better you will understand the contextual meaning of the verbs that convey these meanings. You can always easily navigate this lesson if you forget or miss something.

Let's start with the verb können - a verb that usually expresses the ability to do something, skill, physical ability, knowledge of something, and sometimes permission to do something. The verb very often appears in the speech of Germans, even where it is not entirely appropriate. For example, as in the last example, where it would be logically correct to put the verb durfen. However, there are things that seem familiar to Germans, despite the general rules of verb usage.

Similar to the wonderful verb discussed above durfen , which also expresses possibility, but this possibility is determined not so much physically as by permission or the right to act. When we say “I can,” we can mean “I am capable” and “I have the right.” Verb durfen refers specifically to the latter, which is its main difference from the verb können.

The next verb is sollen . It expresses, as a rule, a commanding nature, a necessity, a demand both from a third party and one’s own (moral duty). In an interrogative sentence, such a verb is used if a certain call or order must follow from the answerer, as well as in cases of some doubt.

Verb mussen similar to a verb sollen, if we consider it from the point of view of the Russian language, since it also expresses an obligation, but the nature of such an obligation is completely different. Often this verb expresses some kind of internal necessity or need, if you like. In some cases, the verb expresses a certain confidence of the speaker.

Verb wollen expresses a desire or intention, and quite a categorical, demanding one. It is opposed to the verb mögen, which expresses a “softer” desire.

Verb mögen also expresses desire, therefore in meaning it is connected with the verb wollen. The preterite conjunctive form of this verb is very often used, which looks like möchte for the first and third persons singular. It should be translated as “would like.” In one of the lessons on polite phrases, we encountered this form. It is also quite common and often appears in requests. In some cases, the meaning expressed by a verb can indicate the likelihood of something. Also verb mögen can be a synonym for the verb lieben, in this case it ceases to express modality.

Finally, the verb lassen can express, in combination with the infinitive, both assumption, permission, and order. As a full verb lassen has the meaning “to leave” and in this case it can no longer be modal.

Knowing modal verbs, you can easily express any request, wish, make it clear to your interlocutor who owes what to whom, etc. This is a very important and not the easiest topic, since there is a lot to remember, and in addition it is necessary to clearly distinguish those situations where it should be used können

Modal verbs are verbs with the meaning of desire, possibility, ability, obligation:

- wollen - want

- können - be able to, be able to

- mussen - to be due, must

- sollen - to be due, must

- durfen -

- mögen -

These verbs are conjugated in a special way:

Some verbs have a single and completely understandable meaning - cf. wollen - want, können - be able, others seem to duplicate each other - cf. mussen - to be due, must and sollen - to be due, must, and still others generally have a whole range of meanings - cf. durfen - be able, have permission, dare, mögen - want, desire; be able; love, like. Let us explain all these meanings.

Verb wollen used in ordinary expressions of will:

- Ich will schlafen. - I want to sleep.

- Willst du nach Berlin fahren? - Do you want to go to Berlin?

In addition, this verb is involved in the formation of the imperative 1st l. plural "wollen wir" - Let's(do not confuse this form with wir wollen - we want):

- Wollen wir eine Pause machen! - Let's take a break!

- Wollen wir tanzen! - Let's Dance!

The verb wollen denotes desire and will in general. And how to express a wish in a polite form, see below (verb mögen).

The phrases “I’m hungry” and “I’m thirsty” in German are not associated with a verb of will, but with indications of hunger or thirst. Wed:

- Ich habe Hunger. - I want to eat.

- Ich habe Durst. - I'm thirsty.

Verb können means opportunity, ability, ability:

- Sie können mit dem Bus fahren. - You can go by bus.

- Ich kann gut schwimmen. - I can swim well/I am a good swimmer.

With language designations, the verb können can be used without another verb:

- Ich kann Russisch und Englisch. - I speak Russian and English.

- Ich kann ein wenig Deutsch. - I speak German a little bit.

The verbs müssen and sollen have the same basic meaning - to be due, must. But the shades of meaning of these verbs are completely different. Mussen means necessity as a result of internal conviction or objective circumstances (cf. the English verb must):

- Ich muss gehen. - I have to go.

- Alle Schüler müssen Hausaufgaben machen. - All schoolchildren must do their homework.

Sollen means necessity as a consequence of some considerations, rules, etc. and expresses a recommendation (cf. the English verb should). This verb is translated into Russian by the impersonal phrase “should”:

- Sie sollen weniger essen. - You should eat less.

- Soll ich meinen Pass zeigen? - Do I need to show my passport?

It is clear that I have no internal need to show my passport, and the need in this case is related to some circumstances or considerations. Compare two examples:

- Christa muss viel arbeiten. - Krista has to work hard.

- Christa soll viel arbeiten. - Krista should work hard.

The first example means that Christe have to work hard, second - what does she care? should to work a lot. You need to pay special attention to the difference between the verbs müssen and sollen in everyday life, since sollen is used in a number of familiar situations:

- Sie sollen nach rechts gehen. - You need to go right.

- Soll ich gleich bezahlen? - Should I pay right away?

- Wo soll ich den Schlüssel lassen? - Where should I leave the key?

The same pair as the verbs müssen and sollen, only in relation to possibility, is formed by the verbs können and dürfen. Verb können means the possibility as a result of free self-determination:

- Ich kann dieses Buch kaufen. - I can buy this book.

- Sie kann Tennis spielen. - She knows how to play tennis.

Verb durfen means possibility as a result of permission, permission:

- Darf ich fragen? - Can I ask?

- Wir dürfen diese Bücher nehmen. - We can borrow these books.

In various everyday matters, dürfen is used:

- Darf ich hinaus? - May go out?

- Darf ich gehen? - Can I go?

And it is no coincidence that on the packaging of low-calorie margarine, etc. for those who like to monitor their weight it is written:

- Du darfst! - You can!

Verb mögen- perhaps the most peculiar of all modal verbs. Firstly, in the present tense it means “to love, like”, etc.:

- Ich mag Fisch. - I like fish.

- Magst du Schwarzbrot? - Do you like black bread?

Secondly, this verb is mostly used in the subjunctive mood of the past tense (preterite) and then means a wish expressed in a polite form:

- Ich möchte diese Jacke kaufen. - I would like to buy this jacket.

- Möchten Sie weiter gehen oder bleiben wir hier? - Would you like to go further, or will we stay here?

The verb mögen in the past subjunctive mood is conjugated as follows:

When expressing any wishes in everyday life, the phrase “ich möchte” actually replaced the direct expression of will “ich will”. So if you want to buy something, watch something, etc., say “ich möchte” - and you can’t go wrong! How can we say: “to want means to be able”? Very simply: Wer will, der kann!

Today it shares second place with Chinese in terms of demand, which is why many “polyglots” are trying to learn it. The second argument in favor of learning the German language is the native country itself - Germany. A high standard of living and hospitality towards emigrants is what is essential to her. But you can’t speak a language without knowing the basic rules of grammar.

What modal verbs exist in the official language of the European Union?

Modal verbs in German are limited in number, which is equal to 8. All “Verben”, in turn, are divided into synonymous pairs, but at the same time they have different purposes.

All pairs are translated into Russian by the same word, but if you use it in the wrong place, a slight confusion may arise, so you need to clearly know where to use the modal verb that is needed in a given situation, and where not.

Correct use of modal verbs

As noted before, modal verbs can easily be divided into synonymous pairs, but how can they be used correctly? This is exactly what needs to be dealt with.

Dürfen (Verb.) is translated as "to be able", but is used in the context of "To be able with the permission of something or someone." As an example, you can give the sentence: “Ich darf nicht mit dir ins Kino gehen, wegen des Verbot meinen Eltern,” and this can be translated as follows: “I won’t be able to go to the cinema with you because of my parents’ ban.”

Können (Verb.) also means “To be able”, but in this case there are two possible uses:

1) To be able to do something, for example, buy a car or something else.

2) To have the ability to do something. The Germans never express the concept of "knowing German" as "Ich kenne/weiß Deutsch", they say "Ich kann Deutsch".

Müssen - Verb., also has several meanings, but is translated: “Must”:

1) Forced to do something under the pressure of certain circumstances.

2) Forced to perform certain actions due to extreme necessity.

3) If the modal verb in German was used in the Konjunktiv II form, then the verb can mean the inevitability of some circumstances.

Sollen - Verb., creates a synonymous pair with the verb "Müssen", but is used within a more rigid framework:

1) Must do something according to clearly established laws or rules.

2) If we speak in an affirmative form, then the meaning of the sentence must be constructed in such a way that a person must demand the fulfillment of certain rules or moral norms.

3) Used as an additional emphasis on the fact that a person is forced to do this action by someone’s order or, possibly, instructions.

Mögen - Verb., which in translation expresses a certain desire of a person, or inclination towards some kind of craft.

Wollen - Verb., but he expresses not so much interest in the object as the desire to get it or the desire to perform some action.

German modal verb conjugation

The German language and its grammar are very diverse. Conjugation is one of the basic rules when studying the section "Modal Verbs in German". The conjugation of these particular verbs has several characteristic features that you need to remember once and not forget again, since they are used quite often. The first and most likely the most important rule is very simple and easy to remember. When conjugating a singular noun in the 1st and 3rd person, the verb does not have any ending, and its root can change, and you just need to remember this. In the already past tense (Präteritum, Perfekt), modal verbs are most often used in Präteritum and are also conjugated a little differently. Their umlauts [ä,ö,ü] disappear and their form begins to resemble Konjuktiv II.

Place of a modal verb in a sentence

Like other verbs in simple sentences, modals take second place in the sentence and play the role of the main verb.

In complex sentences where there are two verbs, the modal verb is the main one, and it changes depending on the subject, and the second verb goes to the very end of the sentence in the initial Infinitiv form.

In the third case, we have a subordinate clause with the conjunction dass/weil/obwohl and others, after which the verb must go to the end. If there are two verbs, and one of them is modal, then the modal verb will go to the very end, and the place in front of it will be taken by the contract verb, and in the initial Infinitiv form.

Well, the very last option that will be considered is the past tense. If a modal verb is used together with an auxiliary, then it has an infinitive form and comes to the end; in second place is an auxiliary verb, the conjugation of which depends on the subject.

Exercises for practicing modal verbs in German

Every person who learns a foreign language must be aware that it is quickly forgotten and requires constant refreshment of knowledge. There are several methods not to forget, and even more - to improve your language. Of course, the most productive thing is to immerse yourself in a language environment, where you have the opportunity to communicate around the clock in this language and improve your knowledge. Not everyone has the opportunity to live and study in one of the German-speaking countries for various reasons, so they have to learn German at home.

Modal verbs - exercises and various tasks to consolidate them - will help you hone your skills and learn how to use sentences with them without errors in construction and conjugation. There are enough grammar textbooks and collections, but it is worth noting several publications, working with which will seem very pleasant and productive. This is "Deutsch. Kurzgrammatik zum Nachschlagen und üben", author - Monika Reimann, as well as "German Grammar" from a Ukrainian author named Zavyalova.

Results

Modal verbs in German play one of the most important roles in structuring text and sentences. Without a doubt, it is impossible to speak correctly in pure German if you do not know the basic rules that should be followed when using sentences with modal verbs. It’s impossible to just start speaking in an unfamiliar language; for this you need to work very hard and fruitfully, because it’s not for nothing that the Germans say: “Ohne Fleis, kein Preis.” This is the equivalent of the Russian proverb: “You can’t even pull a fish out of the pond without effort.”

Details Category: German modal verbsModal verbs express not the action itself, but the attitude towards the action (i.e. the possibility, necessity, desirability of performing the action), therefore they are usually used in a sentence with the infinitive of another verb expressing the action.

Modal verbs include the following verbs:

können dürfen müssen sollen mögen wollen

The conjugated modal verb stands In second place in a sentence, and the infinitive of the semantic verb is last in a sentence and is used without the particle zu.

können- be able, be able, be able (possibility due to objective circumstances)

durfen- 1) be able - dare, have permission (possibility based on “someone else’s will”) 2) when denied, expresses prohibition - “impossible”, “not allowed”

mussen- 1) obligation, necessity, need, conscious duty 2) when negated, “müssen” is often replaced by the verb “brauchen + zu Infinitiv)

sollen- 1) obligation based on “someone else’s will” - order, instruction, instruction 2) in a question (direct or indirect) is not translated (expresses “request for instructions, instructions”)

wollen- 1) want, intend, gather 2) invitation to joint action

mögen- 1) “would like” - in the form möchte (politely expressed desire in the present tense) 2) love, like - in its own meaning (when used without an accompanying infinitive)

The meaning of modal verbs in German

durfen

a) have permission or right

In diesem Park durfen Kinder spielen. - In this park for children allowed play.

b) prohibit (always in negative form)

Bei Rot darf man die Straße nothingüberqueren. - Street it is forbidden cross against the lights

können

a) have the opportunity

In einem Jahr können wir das Haus bestimmt teurer verkaufen. - In a year we will definitely we can sell the house for more money.

b) have the ability to do something

Er kann gut Tennis spielen. - He can play tennis well.

mögen

a) have/not have an inclination, disposition towards something.

Ich mag mit dem neuen Kollegen nicht zusammenarbeiten. - I don't like work with someone new.

b) the same meaning, but the verb acts as a full-valued one

Ich mag keine Schlagsahne! - I don't I love whipped cream!

The modal verb mögen is most often used in the subjunctive form (conjunctive) möchte - would like. The personal endings for this form are the same as for other modal verbs in the present:

ich möchte, du möchtest, etc.

c) have a desire

Wir möchten ihn gern kennen lernen. - We would you like to meet him.

Ich möchte Deutsch sprechen.— I I would like to speak German.

Du möchtest Arzt werden. - You I would like to To become a doctor.

Er möchte auch commen. - He too I would like to come.

mussen

a) be forced to perform an action under the pressure of external circumstances

Mein Vater ist krank, ich muss nach Hause fahren. - My father is sick, I must to drive home.

b) to be forced to perform an action out of necessity

Nach dem Unfall mussten wir zu Fuß nach Hause gehen. - After the accident we must were walk home.

c) accept the inevitability of what happened

Das must ja so kommen, wir haben es geahnt. - This should have happen, we saw it coming.

d) Instead of müssen with negation there is = nicht brauchen + zu + Infinitiv

Mein Vater ist wieder gesund, ich brauche nicht nach Hause zu fahren. - My father is healthy again, I don’t need to to drive home.

sollen

a) require action to be performed in accordance with commandments, laws

Du sollst nicht toten. - You do not must kill.

b) demand the performance of an action in accordance with duty, morality

Jeder soll die Lebensart des anderen anerkennen. - Every must respect the other's way of life.

c) emphasize that the action is performed on someone’s order or instruction

Ich soll nüchtern zur Untersuchung kommen. Das hat der Arzt gesagt. - I must come on an empty stomach for the study. That's what the doctor said.

wollen

a) express a strong desire

Ich will dir die Wahrheit sagen. - I Want tell you the truth.

b) communicate your intention to do something, plans for the future

I'm December wollen wir in das neue Haus einziehen. - In December we we want move into a new house.

In some cases, the main verb may be omitted:

Ich muss nach Hause (gehen). Sie kann gut Englisch (sprechen). Er will in die Stadt (fahren). Ich mag keine Schlagsahne (essen).

A modal verb can be used without a main verb if the main verb is mentioned in the previous context:

Ich kann nicht gut kochen. Meine Mutter konnte es auch nicht. Wir haben es beide nicht gut gekonnt.

Conjugation of modal verbs

Conjugation tables for modal verbs need to be memorized.

Conjugation table for modal verbs in the present tense

Pronoun man in combination with modal verbs it is translated by impersonal constructions:

man kann - you can

man kann nicht - impossible, impossible

man darf - possible, allowed

man darf nicht - impossible, not allowed

man muss - necessary, necessary

man muss nicht - not necessary, not necessary

man soll - should, must

man soll nicht - should not

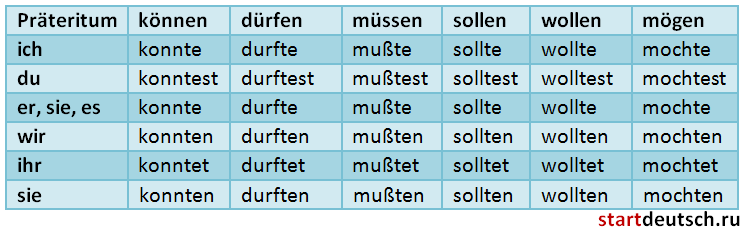

Conjugation table for modal verbs in the past tense Präteritum

Modal verbs in the past tense are most often used in Präteritum. In other past tenses, modal verbs are practically not used.

Place of a modal verb in a simple sentence

1. The modal verb is in a simple sentence In second place.

The second place in the sentence is occupied by the conjugated part of the predicate - the auxiliary verb haben. The modal verb is used in the infinitive and follows the full verb, occupying the last place in the sentence.

Präsens: Der Arbeiter will den Meister sprechen .

Präteritum: Der Arbeiter Wollte den Meister sprechen .

Perfect: Der Arbeiter hat den Meister sprechen wollen .

Plusquamperfect: Der Arbeiter hatte den Meister sprechen wollen .

Place of a modal verb in a subordinate clause

1. Modal verb in the form of present or imperfect stands in a subordinate clause last.

2. If a modal verb is used in perfect or plusquaperfect form, then it is also worth in the infinitive form in last place. The conjugated part of the predicate - the auxiliary verb - comes before both infinitives.

Präsens besuchen kann .

Präteritum: Es ist schade, dass er uns nicht be suchen konnte.

Perfect: Es ist schade, dass er uns nicht hat besuchen können.

Plusquamperfect: Es ist schade, dass er uns nicht hatte besuchen können.