Brodsky on the role of literature and "the face of a non-general expression". Brodsky's famous speech at the Nobel Prize ceremony Brodsky's Nobel speech analysis

"If art teaches something (and the artist - first of all), then it is the particulars of human existence. Being the most ancient - and most literal - form of private enterprise, it voluntarily or involuntarily encourages in a person precisely his sense of individuality, uniqueness, separateness - turning him from a social animal into a person. Many things can be shared: bread, bed, beliefs, beloved - but not a poem by, say, Rainer Maria Rilke. entering into direct relations with it without intermediaries. For this reason, art in general, literature in particular, and poetry in particular, are disliked by zealots of the common good, rulers of the masses, heralds of historical necessity. For where art has passed, where a poem has been read, they they find in place of the expected consent and unanimity - indifference and disagreement, in place of determination to act - inattention and disgust. In other words, in the zeros with which the zealots of the common good and the rulers of the masses strive to operate, art enters a "dot-dot-comma with a minus", turning each zero into a human face, if not always attractive. " Joseph Brodsky, "Nobel Lecture" ( 1987)

Joseph Brodsky

Nobel lecture

For a private person who has preferred this whole life to any public role, for a person who has gone quite far in this preference - and in particular from his homeland, for it is better to be the last loser in a democracy than a martyr or ruler of thoughts in a despotism - to be suddenly on this podium is a great awkwardness and test.

This feeling is aggravated not so much by the thought of those who stood here before me, but by the memory of those whom this honor has passed, who could not turn, as they say, "urbi et orbi" from this rostrum and whose general silence seems to be looking for and not finds a way out in you.

The only thing that can reconcile you to such a situation is the simple consideration that - for stylistic reasons in the first place - a writer cannot speak for a writer, especially a poet for a poet; that, if Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, Robert Frost, Anna Akhmatova, Winston Auden were on this podium, they would involuntarily speak for themselves, and, perhaps, they would also experience some embarrassment.

These shadows confuse me all the time, they confuse me to this day. In any case, they do not encourage me to be eloquent. In my best moments, I seem to myself, as it were, their sum - but always less than any of them taken separately. For it is impossible to be better than them on paper; it is impossible to be better than them in life, and it is precisely their lives, no matter how tragic and bitter they may be, that make me often - apparently, more often than I should - regret the passage of time. If that light exists - and I can no more deny them the possibility of eternal life than to forget their existence in this one - if that light exists, then they, I hope, will forgive me also the quality of what I am about to state: in after all, the dignity of our profession is not measured by behavior on the podium.

I named only five - those whose work and whose destinies are dear to me, if only because, without them, I would not be worth much as a person and as a writer: in any case, I would not be standing here today. Them, these shadows - better: light sources - lamps? stars? -- there were, of course, more than five, and any of them is capable of dooming to absolute dumbness. Their number is great in the life of any conscious writer; in my case, it doubles, thanks to the two cultures to which I belong by the will of fate. Nor does it make things any easier to think about contemporaries and fellow writers in both these cultures, about poets and prose writers, whose talents I value more than my own and who, if they were on this platform, would have already moved on to business, because they have more, what to say to the world than mine.

Therefore, I will allow myself a number of remarks - perhaps discordant, confused and which may puzzle you with their incoherence. However, the amount of time allotted for me to collect my thoughts, and my very profession, will protect me, I hope, at least in part from reproaches of randomness. A man of my profession seldom claims to be systematic in thought; at worst, he pretends to be a system. But this, as a rule, is borrowed from him: from the environment, from the social structure, from studying philosophy at a tender age. Nothing convinces the artist more of the randomness of the means that he uses to achieve this or that - even a permanent - goal, than the creative process itself, the process of writing. Poems, according to Akhmatova, really grow out of rubbish; the roots of prose are no more noble.

If art teaches something (and the artist in the first place), then it is precisely the particulars of human existence. Being the most ancient - and most literal - form of private enterprise, it wittingly or unwittingly encourages in a person precisely his sense of individuality, uniqueness, separateness - turning him from a social animal into a person. Much can be shared: bread, bed, beliefs, beloved - but not a poem by, say, Rainer Maria Rilke. Works of art, literature in particular, and a poem in particular, address a person tete-a-tete, entering into direct relations with him, without intermediaries. That is why art in general, literature in particular, and poetry in particular, are disliked by zealots of the common good, rulers of the masses, heralds of historical necessity. For where art has passed, where a poem has been read, they find in the place of the expected agreement and unanimity - indifference and disagreement, in the place of determination to action - inattention and disgust. In other words, in the zeros with which the zealots of the common good and the rulers of the masses strive to operate, art inscribes a "dot-dot-comma with a minus", turning each zero into a human face, if not always attractive.

The great Baratynsky, speaking of his Muse, described her as possessing "an uncommon expression on her face." It seems that the meaning of individual existence lies in the acquisition of this non-general expression, for we are, as it were, genetically prepared for this non-commonality. Regardless of whether a person is a writer or a reader, his task is to live his own, and not imposed or prescribed from the outside, even the most noble-looking life. For each of us has only one, and we know well how it all ends. It would be a shame to waste this one chance on repeating someone else's appearance, someone else's experience, on a tautology - all the more insulting because the heralds of historical necessity, at whose instigation a person is ready to agree to this tautology, will not lie down with him in the coffin and will not say thank you.

Language and, I think, literature are things more ancient, inevitable, durable than any form of social organization. The indignation, irony or indifference expressed by literature towards the state is, in essence, the reaction of the permanent, or rather, the infinite, in relation to the temporal, the limited. At least as long as the state allows itself to interfere in the affairs of literature, literature has the right to interfere in the affairs of the state. A political system, a form of social organization, like any system in general, is, by definition, a form of the past tense, trying to impose itself on the present (and often the future), and a person whose profession is language is the last one who can afford to forget about it. . The real danger for the writer is not only the possibility (often a reality) of persecution by the state, but the possibility of being hypnotized by him, the state, monstrous or changing for the better - but always temporary - outlines.

The philosophy of the state, its ethics, not to mention its aesthetics, are always "yesterday"; language, literature - always "today" and often - especially in the case of the orthodoxy of one system or another - even "tomorrow". One of the merits of literature lies in the fact that it helps a person to clarify the time of his existence, to distinguish himself in the crowd of both his predecessors and his own kind, to avoid tautology, that is, a fate otherwise known under the honorary name of "victims of history". Art in general, and literature in particular, is remarkable and differs from life in that it always avoids repetition. In everyday life, you can tell the same joke three times and three times, causing laughter, and turn out to be the soul of society. In art, this form of behavior is called "cliché". Art is a recoilless tool, and its development is determined not by the individuality of the artist, but by the dynamics and logic of the material itself, the previous history of means that require finding (or suggesting) every time a qualitatively new aesthetic solution. Possessing its own genealogy, dynamics, logic and future, art is not synonymous, but, at best, parallel to history, and its mode of existence is the creation of a new aesthetic reality every time. That is why it often turns out to be "ahead of progress", ahead of history, the main instrument of which is—shouldn't we clarify Marx? -- it's a cliché.

Selected passages from the Nobel speech of Joseph Brodsky

The 75th anniversary of the birth of Joseph Brodsky in Russia is celebrated modestly. On the one hand, this great Russian poet glorified our country to the whole world, on the other hand, with all his soul he hated the Soviet state, in which many today are again looking for support. Why literature should not speak the "language of the people" and how good books protect against propaganda - these reflections from the poet's Nobel speech are always relevant, but especially today.

If art teaches something (and the artist - first of all), then it is the particulars of human existence. Being the most ancient - and most literal - form of private enterprise, it wittingly or unwittingly encourages in a person precisely his sense of individuality, uniqueness, separateness - turning him from a social animal into a person.

Much can be shared: bread, bed, beliefs, beloved - but not a poem by, say, Rainer Maria Rilke.

Works of art, literature in particular, and a poem in particular, address a person tete-a-tete, entering into direct relations with him, without intermediaries. That is why art in general, literature in particular, and poetry in particular, are disliked by zealots of the common good, rulers of the masses, heralds of historical necessity. For where art has passed, where a poem has been read, they find in the place of the expected agreement and unanimity - indifference and disagreement, in the place of determination to action - inattention and disgust.

In other words, in the zeros with which the zealots of the common good and the rulers of the masses strive to operate, art inscribes a “dot-dot-comma with a minus”, turning each zero into a human face, if not always attractive.

... The Great Baratynsky, speaking of his Muse, described her as having "a non-general expression on her face." It seems that the meaning of individual existence lies in the acquisition of this non-general expression, for we are, as it were, genetically prepared for this non-commonality. Regardless of whether a person is a writer or a reader, his task is to live his own, and not imposed or prescribed from the outside, even the most noble-looking life.

For each of us has only one, and we know well how it all ends. It would be a shame to waste this only chance on repeating someone else's appearance, someone else's experience, on a tautology - all the more insulting because the heralds of historical necessity, at whose instigation a person is ready to agree to this tautology, will not lie down with him in the coffin and will not say thank you.

... Language and, I think, literature are things more ancient, inevitable, durable than any form of social organization. The indignation, irony or indifference expressed by literature towards the state is, in essence, the reaction of the permanent, or rather, the infinite, in relation to the temporal, the limited.

At least as long as the state allows itself to interfere in the affairs of literature, literature has the right to interfere in the affairs of the state.

A political system, a form of social organization, like any system in general, is, by definition, a form of the past tense trying to impose itself on the present (and often the future), and a person whose profession is language is the last one who can afford to forget about it. The real danger for the writer is not only the possibility (often a reality) of persecution by the state, but the possibility of being hypnotized by him, the state, by monstrous or changing for the better - but always temporary - outlines.

... The philosophy of the state, its ethics, not to mention its aesthetics, are always “yesterday”; language, literature - always "today" and often - especially in the case of the orthodoxy of one system or another - even "tomorrow".

One of the merits of literature lies in the fact that it helps a person to clarify the time of his existence, to distinguish himself in the crowd of both his predecessors and his own kind, to avoid tautology, that is, a fate otherwise known under the honorary name of “victims of history”.

...Today, the assertion is extremely widespread that a writer, a poet in particular, should use the language of the street, the language of the crowd, in his works. For all its seeming democracy and tangible practical benefits for the writer, this statement is absurd and represents an attempt to subordinate art, in this case literature, to history.

Only if we have decided that it is time for "sapiens" to stop its development, should literature speak the language of the people. Otherwise, the people should speak the language of literature.

Any new aesthetic reality clarifies ethical reality for a person. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics; the concepts of "good" and "bad" are primarily aesthetic concepts, anticipating the categories of "good" and "evil". In ethics, not "everything is allowed" because in aesthetics not "everything is allowed", because the number of colors in the spectrum is limited. An unintelligent baby, crying out against a stranger or, on the contrary, reaching out to him, rejects him or is drawn to him, instinctively making an aesthetic choice, and not a moral one.

…Aesthetic choice is always individual, and aesthetic experience is always a private experience. Any new aesthetic reality makes the person experiencing it even more private, and this privateness, sometimes taking on the form of a literary (or some other) taste, can in itself be, if not a guarantee, then at least a form of protection against enslavement. For a man of taste, in particular literary taste, is less receptive to the repetition and rhythmic incantations inherent in any form of political demagoguery.

It's not so much that virtue is no guarantee of a masterpiece, but that evil, especially political evil, is always a bad stylist.

The richer the aesthetic experience of the individual, the firmer his taste, the clearer his moral choice, the freer he is - although, perhaps, not happier.

... In the history of our species, in the history of "sapiens", the book is an anthropological phenomenon, similar in essence to the invention of the wheel. Arised to give us an idea not so much about our origins as about what this "sapiens" is capable of, the book is a means of moving through the space of experience with the speed of a page turning. This displacement, in turn, like any displacement, turns into a flight from a common denominator, from an attempt to impose the denominator of this trait, which had not previously risen above the waist, on our heart, our consciousness, our imagination.

This flight is a flight towards a non-general expression of the face, towards the numerator, towards the personality, towards the particular. In whose image and likeness we were created, there are already five billion of us, and a person has no other future than that outlined by art. Otherwise, the past awaits us - first of all, the political one, with all its mass police delights.

In any case, the situation in which art in general and literature in particular is the property (prerogative) of a minority seems to me unhealthy and threatening.

I do not call for the replacement of the state by a library - although this thought has repeatedly visited me - but I have no doubt that if we choose our rulers on the basis of their reading experience, and not on the basis of their political programs, there would be less grief on earth.

I think that the potential master of our destinies should be asked first of all not about how he imagines the course of foreign policy, but about how he relates to Stendhal, Dickens, Dostoevsky. If only by the mere fact that the daily bread of literature is precisely human diversity and ugliness, it, literature, turns out to be a reliable antidote to any - known and future - attempts of a total, mass approach to solving the problems of human existence.

As a system of moral insurance, at least, it is much more effective than this or that system of beliefs or philosophical doctrine.

Because there can be no laws that protect us from ourselves, no criminal code provides for punishment for crimes against literature. And among these crimes, the most serious is non-censorship restrictions, etc., not committing books to the fire.

There is a more serious crime - the neglect of books, their non-reading. For this crime, this person pays with his whole life: if a nation commits this crime, it pays for it with its history.

Living in the country in which I live, I would be the first to believe that there is a certain proportion between the material well-being of a person and his literary ignorance; What keeps me from doing this, however, is the history of the country in which I was born and raised. For reduced to a causal minimum, to a rough formula, Russian tragedy is precisely the tragedy of a society in which literature turned out to be the prerogative of a minority: the famous Russian intelligentsia.

I don’t want to expand on this topic, I don’t want to darken this evening with thoughts about tens of millions of human lives ruined by millions - because what happened in Russia in the first half of the 20th century happened before the introduction of automatic small arms - in the name of the triumph of political doctrine , whose failure already lies in the fact that it requires human sacrifices for its implementation. I will only say that - not from experience, alas, but only theoretically - I believe that it is more difficult for a person who has read Dickens to shoot his own kind in the name of any idea whatever than for a person who has not read Dickens.

And I'm talking specifically about reading Dickens, Stendhal, Dostoyevsky, Flaubert, Balzac, Melville, etc., i.e. literature, not about literacy, not about education. A literate, educated person may well, having read this or that political treatise, kill his own kind and even experience the delight of conviction.

Lenin was literate, Stalin was literate, Hitler too; Mao Zedong, so he even wrote poetry; the list of their victims, however, far exceeds the list of what they have read.

For a private person who has preferred this whole life to any public role, for a person who has gone quite far in this preference - and in particular from his homeland, for it is better to be the last loser in democracy than a martyr or ruler of thoughts in despotism - to suddenly find yourself on this podium - a great awkwardness and test.

This feeling is aggravated not so much by the thought of those who stood here before me, but by the memory of those whom this honor has passed, who could not turn, as they say, “urbi et orbi” from this rostrum and whose general silence seems to be looking for and not finds a way out in you.

The only thing that can reconcile you to such a situation is the simple consideration that - for reasons primarily of style - a writer cannot speak for a writer, especially a poet for a poet; that, if Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, Robert Frost, Anna Akhmatova, Winston Auden were on this podium, they would involuntarily speak for themselves, and, perhaps, they would also experience some embarrassment.

These shadows confuse me all the time, they confuse me to this day. In any case, they do not encourage me to be eloquent. In my best moments, I seem to myself, as it were, their sum - but always less than any of them taken separately. For it is impossible to be better than them on paper; it is impossible to be better than them in life, and it is their lives, no matter how tragic and bitter they are, that make me often - apparently more often than I should - regret the passage of time. If that light exists - and I can no more deny them the possibility of eternal life than to forget their existence in this one - if that light exists, then they will, I hope, forgive me also the quality of what I am about to state: after all It is not by behavior on the podium that the dignity of our profession is measured.

I named only five - those whose work and whose fates are dear to me, if only because, without them, I would not be worth much as a person and as a writer: in any case, I would not be standing here today. They, these shadows are better: light sources - lamps? stars? - there were, of course, more than five, and any of them is capable of dooming to absolute dumbness. Their number is great in the life of any conscious writer; in my case, it doubles, thanks to the two cultures to which I belong by the will of fate. Nor does it make things any easier to think about contemporaries and fellow writers in both these cultures, about poets and prose writers, whose talents I value more than my own and who, if they were on this platform, would have already moved on to business, because they have more, what to say to the world than mine.

Therefore, I will allow myself a number of remarks - perhaps discordant, confused and which may puzzle you with their incoherence. However, the amount of time allotted for me to collect my thoughts, and my very profession, will protect me, I hope, at least in part from reproaches of randomness. A man of my profession seldom claims to be systematic in thought; at worst, he pretends to be a system. But this, as a rule, is borrowed from him: from the environment, from the social structure, from studying philosophy at a tender age. Nothing convinces the artist more of the randomness of the means that he uses to achieve this or that - even if permanent - goal, than the very creative process, the process of writing. Poems, according to Akhmatova, really grow out of rubbish; the roots of prose are no more noble.

If art teaches something (and the artist in the first place), then it is precisely the particulars of human existence. Being the most ancient - and most literal - form of private enterprise, it wittingly or unwittingly encourages in a person precisely his sense of individuality, uniqueness, separateness - turning him from a social animal into a person. Much can be shared: bread, bed, beliefs, beloved - but not a poem by, say, Rainer Maria Rilke. Works of art, literature in particular, and a poem in particular, address a person tete-a-tete, entering into direct relations with him, without intermediaries. That is why art in general, literature in particular, and poetry in particular, are disliked by zealots of the common good, rulers of the masses, heralds of historical necessity. For where art has passed, where a poem has been read, they find in the place of the expected agreement and unanimity - indifference and disagreement, in the place of determination to action - inattention and disgust. In other words, in the zeros with which the zealots of the common good and the rulers of the masses strive to operate, art inscribes a “dot-dot-comma with a minus”, turning each zero into a human face, if not always attractive.

The great Baratynsky, speaking of his Muse, described her as possessing "an uncommon expression on her face." It seems that the meaning of individual existence lies in the acquisition of this non-general expression, for we are, as it were, genetically prepared for this non-commonality. Regardless of whether a person is a writer or a reader, his task is to live his own, and not imposed or prescribed from the outside, even the most noble-looking life. For each of us has only one, and we know well how it all ends.

It would be a shame to waste this only chance on repeating someone else's appearance, someone else's experience, on a tautology - all the more insulting because the heralds of historical necessity, at whose instigation a person is ready to agree to this tautology, will not lie down with him in the coffin and will not say thank you.

Language and, I think, literature are things more ancient, inevitable, durable than any form of social organization. The indignation, irony or indifference expressed by literature in relation to the state is, in essence, the reaction of the permanent, or rather, the infinite, in relation to the temporary, the limited. At least as long as the state allows itself to interfere in the affairs of literature, literature has the right to interfere in the affairs of the state.

A political system, a form of social organization, like any system in general, is, by definition, a form of the past tense trying to impose itself on the present (and often the future), and a person whose profession is language is the last one who can afford to forget about it. The real danger for the writer is not only the possibility (often a reality) of persecution by the state, but the possibility of being hypnotized by him, the state, by monstrous or changing for the better - but always temporary - outlines.

The philosophy of the state, its ethics, not to mention its aesthetics, are always "yesterday"; language, literature - always "today" and often - especially in the case of the orthodoxy of one system or another - even "tomorrow". One of the merits of literature lies in the fact that it helps a person to clarify the time of his existence, to distinguish himself in the crowd of both his predecessors and his own kind, to avoid tautology, that is, a fate otherwise known under the honorary name of “victims of history”.

Art in general, and literature in particular, is remarkable and differs from life in that it always avoids repetition. In everyday life, you can tell the same joke three times and three times, causing laughter, and turn out to be the soul of society. In art, this form of behavior is called "cliché". Art is a recoilless tool, and its development is determined not by the individuality of the artist, but by the dynamics and logic of the material itself, the previous history of means that require finding (or suggesting) every time a qualitatively new aesthetic solution.

Possessing its own genealogy, dynamics, logic and future, art is not synonymous, but, at best, parallel to history, and its mode of existence is the creation of a new aesthetic reality every time. That is why it often turns out to be "ahead of progress", ahead of history, the main instrument of which is - should we clarify Marx? - it's a cliché.

To date, the assertion is extremely widespread that a writer, a poet in particular, should use the language of the street, the language of the crowd, in his works. For all its seeming democracy and tangible practical benefits for the writer, this statement is absurd and represents an attempt to subordinate art, in this case literature, to history. Only if we have decided that it is time for "sapiens" to stop its development, should literature speak the language of the people.

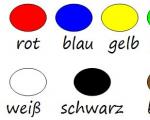

Otherwise, the people should speak the language of literature. Any new aesthetic reality clarifies ethical reality for a person. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics; the concepts of "good" and "bad" are primarily aesthetic concepts, anticipating the categories of "good" and "evil". In ethics, not "everything is allowed" because in aesthetics not "everything is allowed", because the number of colors in the spectrum is limited. An unintelligent baby, crying out against a stranger or, on the contrary, reaching out to him, rejects him or is drawn to him, instinctively making an aesthetic choice, and not a moral one.

Aesthetic choice is always individual, and aesthetic experience is always a private experience. Any new aesthetic reality makes the person experiencing it even more private, and this privateness, sometimes taking the form of a literary (or some other) taste, can already in itself be, if not a guarantee, then at least a form of protection against enslavement. For a man of taste, in particular literary taste, is less receptive to the repetition and rhythmic incantations inherent in any form of political demagoguery.

It's not so much that virtue is no guarantee of a masterpiece, but that evil, especially political evil, is always a bad stylist. The richer the aesthetic experience of the individual, the firmer his taste, the clearer his moral choice, the freer he is - although, perhaps, not happier.

It is in this rather applied than Platonic sense that Dostoevsky's remark that "beauty will save the world" or Matthew Arnold's statement that "poetry will save us" should be understood. The world will probably not be saved, but an individual person can always be saved. The aesthetic sense in a person develops very rapidly, because, even without being fully aware of what he is and what he really needs, a person, as a rule, instinctively knows what he does not like and what does not suit him. In the anthropological sense, I repeat, man is an aesthetic being before he is ethical.

Art, therefore, literature in particular, is not a by-product of species development, but exactly the opposite. If what distinguishes us from other representatives of the animal kingdom is speech, then literature, and in particular poetry, being the highest form of literature, is, roughly speaking, our species goal.

I am far from the idea of universal teaching of versification and composition; nevertheless, the division of people into intelligentsia and everyone else seems to me unacceptable. Morally, this division is similar to the division of society into the rich and the poor; but if some purely physical, material justifications are still conceivable for the existence of social inequality, they are unthinkable for intellectual inequality.

In what-what, and in this sense, equality is guaranteed to us by nature. This is not about education, but about the formation of speech, the slightest proximity of which is fraught with an invasion of a person's life of a false choice. The existence of literature implies existence at the level of literature - and not only morally, but also lexically.

If a piece of music still leaves a person with the opportunity to choose between the passive role of a listener and an active performer, a work of literature - art, according to Montale, hopelessly semantic - dooms him to the role of only a performer.

It seems to me that a person should act in this role more often than in any other. Moreover, it seems to me that as a result of the population explosion and the ever-increasing atomization of society associated with it, that is, with the ever-increasing isolation of the individual, this role is becoming more and more inevitable.

I don't think I know more about life than anyone my age, but it seems to me that a book is more reliable as an interlocutor than a friend or lover. A novel or a poem is not a monologue, but a conversation between a writer and a reader - a conversation, I repeat, extremely private, excluding everyone else, if you like - mutually misanthropic. And at the moment of this conversation, the writer is equal to the reader, as, indeed, vice versa, regardless of whether he is a great writer or not.

This equality is the equality of consciousness, and it remains with a person for life in the form of a memory, vague or distinct, and sooner or later, by the way or inopportunely, determines the individual's behavior. This is what I mean when I speak of the role of the performer, all the more natural since a novel or a poem is the product of the mutual loneliness of writer and reader.

In the history of our species, in the history of "sapiens", the book is an anthropological phenomenon, similar in essence to the invention of the wheel. Arised to give us an idea not so much about our origins as about what this "sapiens" is capable of, the book is a means of moving through the space of experience with the speed of a page turning. This displacement, in turn, like any displacement, turns into a flight from a common denominator, from an attempt to impose the denominator of this trait, which had not previously risen above the waist, on our heart, our consciousness, our imagination. This flight is a flight towards a non-general expression of the face, towards the numerator, towards the personality, towards the particular. In whose image and likeness we were created, there are already five billion of us, and a person has no other future than that outlined by art. Otherwise, the past awaits us - first of all, the political one, with all its massive police delights.

In any case, the situation in which art in general and literature in particular is the property (prerogative) of a minority seems to me unhealthy and threatening. I do not call for the replacement of the state by a library - although this thought has repeatedly visited me - but I have no doubt that if we choose our rulers on the basis of their reading experience, and not on the basis of their political programs, there would be less grief on earth.

I think that the potential master of our destinies should be asked first of all not about how he imagines the course of foreign policy, but about how he relates to Stendhal, Dickens, Dostoevsky. If only by the mere fact that the daily bread of literature is precisely human diversity and ugliness, it, literature, turns out to be a reliable antidote to any - known and future - attempts of a total, mass approach to solving the problems of human existence. As a system of moral insurance, at least, it is much more effective than this or that system of beliefs or philosophical doctrine.

Because there can be no laws that protect us from ourselves, no criminal code provides for punishment for crimes against literature. And among these crimes, the most serious is non-censorship restrictions, etc., not committing books to the fire.

There is a more serious crime - the neglect of books, their non-reading. This person pays for this crime with his whole life: if a nation commits this crime, it pays for it with its history. Living in the country in which I live, I would be the first to believe that there is a certain proportion between the material well-being of a person and his literary ignorance; What keeps me from doing this, however, is the history of the country in which I was born and raised.

For reduced to a causal minimum, to a rough formula, Russian tragedy is precisely the tragedy of a society in which literature turned out to be the prerogative of a minority: the famous Russian intelligentsia.

I don’t want to expand on this topic, I don’t want to darken this evening with thoughts about tens of millions of human lives ruined by millions - because what happened in Russia in the first half of the 20th century happened before the introduction of automatic small arms - in the name of the triumph of political doctrine , whose failure already lies in the fact that it requires human sacrifices for its implementation.

I will only say that - not from experience, alas, but only theoretically - I believe that it is more difficult for a person who has read Dickens to shoot his own kind in the name of any idea whatever than for a person who has not read Dickens. And I'm talking specifically about reading Dickens, Stendhal, Dostoyevsky, Flaubert, Balzac, Melville, etc., i.e. literature, not about literacy, not about education. A literate, educated person may well, having read this or that political treatise, kill his own kind and even experience the delight of conviction. Lenin was literate, Stalin was literate, Hitler too; Mao Zedong, so he even wrote poetry; the list of their victims, however, far exceeds the list of what they have read.

However, before turning to poetry, I would like to add that it would be wise to regard the Russian experience as a warning, if only because the social structure of the West is still generally similar to that which existed in Russia before 1917. (This, by the way, explains the popularity of the Russian psychological novel of the 19th century in the West and the comparative failure of contemporary Russian prose.

The public relations that developed in Russia in the 20th century seem to the reader no less outlandish than the names of the characters, preventing him from identifying himself with them. than exists today in the US or the UK. In other words, a dispassionate person might notice that, in a certain sense, the 19th century in the West is still going on.

In Russia it ended; and if I say that it ended in tragedy, it is primarily because of the number of human casualties that the resulting social and chronological change entailed. In a real tragedy, it is not the hero who perishes - the choir perishes.

Although for a person whose native language is Russian, talking about political evil is as natural as digestion, I would now like to change the subject. The disadvantage of talking about the obvious is that they corrupt the mind with their ease, with their easily acquired sense of being right. This is their temptation, which is similar in nature to the temptation of a social reformer who breeds this evil.

Awareness of this temptation and repulsion from it are to a certain extent responsible for the fate of many of my contemporaries, not to mention fellow writers, responsible for the literature that arose from under their feathers. She, this literature, was not an escape from history, nor a stifling of memory, as it may seem from the outside.

“How can you compose music after Auschwitz?” - Adorno asks, and a person familiar with Russian history can repeat the same question, replacing the name of the camp in it - to repeat it, perhaps even with more right, because the number of people who perished in Stalin's camps far exceeds the number of perished in German . “How can you eat lunch after Auschwitz?” - once remarked the American poet Mark Strand. The generation to which I belong, at any rate, proved capable of composing this music.

This generation - the generation that was born just when the Auschwitz crematoria were operating at full capacity, when Stalin was at the zenith of godlike, absolute, nature itself, it seemed, sanctioned power, appeared in the world, apparently to continue what theoretically should have been break off in these crematoria and in the unmarked common graves of the Stalinist archipelago.

The fact that not everything was interrupted - at least in Russia - is in no small measure the merit of my generation, and I am no less proud of my belonging to it than of the fact that I am standing here today. And the fact that I'm standing here today is a recognition of the merits of this generation to culture; remembering Mandelstam, I would add - in front of world culture.

Looking back, I can say that we started from an empty place - more precisely, from a place frightening in its emptiness, and that, more intuitively than consciously, we aimed precisely at recreating the effect of the continuity of culture, at restoring its forms and paths, at filling its few surviving and often completely compromised forms by our own, new or what seemed to us to be such, modern content.

There was probably another path - the path of further deformation, the poetics of fragments and ruins, minimalism, stifled breath. If we abandoned it, it was not at all because it seemed to us a way of self-dramatization, or because we were extremely animated by the idea of preserving the hereditary nobility of the forms of culture known to us, equivalent in our minds to forms of human dignity.

We abandoned it, because the choice was not really ours, but the choice of culture - and this choice was again aesthetic, not moral. Of course, it is more natural for a person to talk about himself not as an instrument of culture, but, on the contrary, as its creator and custodian.

But if I say the opposite today, it is not because there is a certain charm in paraphrasing Plotinus, Lord Shaftesbury, Schelling or Novalis at the end of the 20th century, but because someone, but a poet always knows that what is in common speech called the voice of the Muse, is in fact the dictate of the language; that language is not his instrument, but he is language's means to continue its existence. Language, on the other hand, even if we imagine it as some kind of animated being (which would only be fair) is not capable of ethical choice.

A person takes up writing a poem for various reasons: to win the heart of his beloved, to express his attitude to the reality surrounding him, whether it be a landscape or a state, to capture the state of mind in which he is currently located, to leave - how he thinks in this minute - footprint on the ground.

He resorts to this form - to a poem - for reasons, most likely, unconsciously mimetic: a black vertical clot of words in the middle of a white sheet of paper, apparently, reminds a person of his own position in the world, of the proportion of space to his body. But regardless of the reasons for which he takes up the pen, and regardless of the effect produced by what comes from his pen, on his audience, however large or small, - the immediate consequence of this enterprise is the feeling of entering into a direct contact with the language, more precisely, the feeling of an immediate falling into dependence on it, on everything that has already been said, written, implemented in it.

This dependence is absolute, despotic, but it also liberates. For, being always older than the writer, language still possesses colossal centrifugal energy imparted to it by its temporal potential—that is, by all the time lying ahead. And this potential is determined not so much by the quantitative composition of the nation that speaks it, although this too, but by the quality of the poem composed on it.

The poet, I repeat, is the means of the existence of language. Or, as the great Auden said, he is the one by whom the language is alive. There will be no me, the writer of these lines, there will be no you, those who read them, but the language in which they are written and in which you read them will remain, not only because the language is more durable than a person, but also because it is better adapted to mutation.

The writer of a poem, however, does not write it because he expects posthumous fame, although he often hopes that the poem will outlive him, if not for long. The writer of a poem writes it because the language tells him or simply dictates the next line.

Starting a poem, the poet, as a rule, does not know how it will end, and sometimes he is very surprised at what happened, because it often turns out better than he expected, often his thought goes further than he expected. This is the moment when the future of a language interferes with its present.

There are, as we know, three methods of knowledge: analytical, intuitive and the method used by the biblical prophets - through revelation. The difference between poetry and other forms of literature is that it uses all three at once (gravitating mainly to the second and third), because all three are given in the language; and sometimes, with the help of one word, one rhyme, the writer of a poem manages to be where no one has been before him - and further, perhaps, than he himself would have wished.

A person who writes a poem writes it primarily because a poem is a colossal accelerator of consciousness, thinking, and attitude. Having experienced this acceleration once, a person is no longer able to refuse to repeat this experience, he falls into dependence on this process, just as one falls into dependence on drugs or alcohol. A person who is in this dependence on language, I believe, is called a poet.

(C) The Nobel Foundation. 1987.